Why K-Scar ?

The border between the two Koreas is a fascinating place.

At first glance, a bizarre mixture of national tragedy, military tensions and over-tourism.

An actual frontline, frozen since 1953. A very real war zone with its military checkpoints, minefields, watchtowers, no-warning shooting zones and razor-wired fences accessible to everyone by subway, a 45 minutes taxi ride, or a half-day package tour from the buzzling Seoul megapolis and its Korean barbecues, k-pop, k-drama, k-cosmetics and k-everything scene.

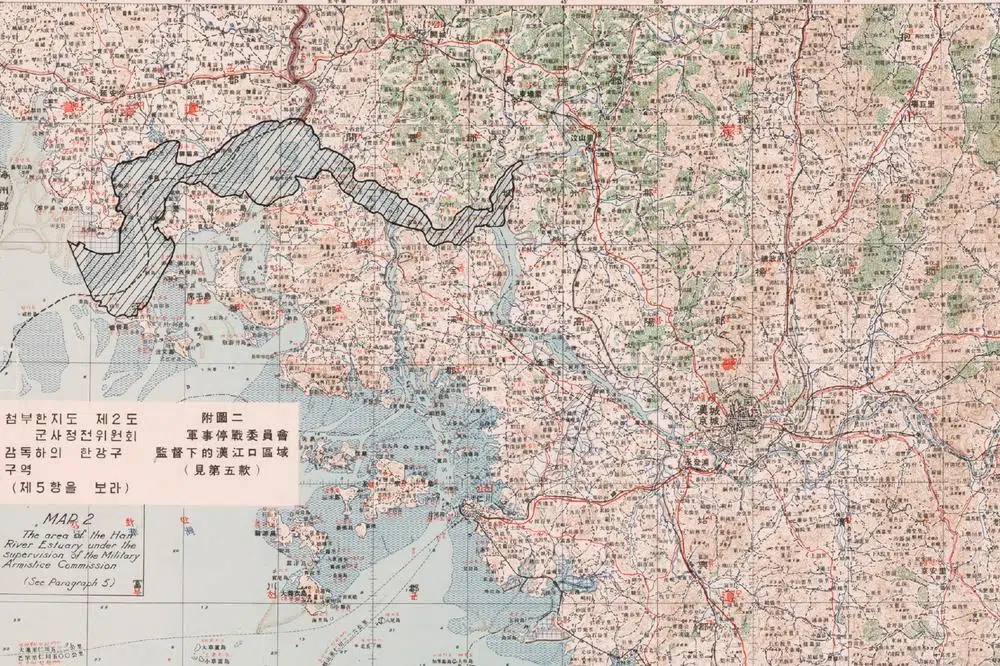

A border that seems strictly demarcated but is in fact much more blurred. There is no demarcation fence in the middle of the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) where North and South Korean soldiers patrol day and night, with the constant risk of running into each other. As for the maritime border, in the shallow waters of the Yellow Sea, it’s even more complicated.

One thing is certain: unlike the Iron Curtain in Europe during the Cold War, which had numerous border crossing points accessible to anyone lucky enough to have a valid visa, this border is impossible to cross in either direction without the near-certainty of being arrested, shot or dying in a thousand other ways in the attempt.

Ever since I arrived in South Korea in 2022, I have been magnetically drawn to the border.

Like many bicultural people, I am attracted to borders. But there is something unique about this one, which has been splitting a single nation, a single culture and a single language in two since 1945, and which continues year after year to distance them from each other, until their similarities will eventually become unrecognisable.

Like many, I was initially excited by the spectacular nature of this militarized, ultra-fortified aberration located less than 50 km from central Seoul.

But after three years of skirting the inter-Korean border from east to west and vice versa, and getting to know my host country, its inhabitants and their feelings a little better, my perception has completely changed.

Now, for me, the border between North and South Korea is a scar across a beautiful face.

An unsightly scar, deep and painful, which many South Koreans have chosen to ignore altogether, while others are doing their best to mitigate by wrapping it in an ointment of green projects, educational facilities, tourism and works of art expressing the pain of separation and the hope of unification with a touching sincerity and fantasy. Others have chosen to exploit it commercially, riding the wave of “dark tourism”. Whatever the case, this scar gives anyone who sees it strong and contradictory sensations. Just like Korea in general.

The K-Scar.

My initial intention was to document only the negative side of the K-Scar: the over-tourism and rip-offs around the DMZ, the hundreds of buses that pour more than a million visitors a year into the Imjingak complex, the surreal “Instagram spots” set up near very real minefields and military installations where photography is in theory forbidden. The bullet or grenade-shaped plastic keyrings (some of them made in China, the enemy during the Korean War) sold in souvenir stores. The fake cardboard soldiers to pose next to for a souvenir photo or selfie. The Starbucks café, opportunely opened in a north-facing observatory, that attracts crowds of tourists since 2024 whereas no one was interested in this place before.

But as I wandered along the DMZ, I realized that these mercantile trappings represent only a very small part of the story, concentrated in a handful of sites close to Seoul.

Everywhere else, the border runs through wild, spectacular mountain landscapes, or through straits separating the remote South Korean islands of the Yellow Sea from a hostile mainland. Access to these places is often difficult, either because they are strictly controlled by the South Korean military, because there are few means of transport, or both.

But it’s when you go to these lesser-known places that you discover the most incredible, touching, sometimes comical but most often ultraviolent border-related stories.

North Korean infiltrators who hide in graves to sleep. A psychosis over a supposed North Korean plan to submerge Seoul under water during the Olympic Games. An “Angels Waterfall” where the most beautiful women in the North Korean army were ordered to bathe naked within sight of soldiers from the South across the border to encourage them to defect. A swimsuit beauty contest organized in retaliation by the South, near a pool specially built for the occasion on top of a mountain visible from the North (all this happened long before the #MeToo movement…)

Some of the little-known observatories I mention on this site also offer sights of life in rural North Korea, with its decrepit villages where all agricultural work is done by hand. These glimpses through a telescope into the hermit kingdom of the Kim dynasty never leave you unscathed. Especially when you turn around and see the forests of high-rise buildings on the outskirts of Seoul.

The aim of my project is to share these stories and feelings with you.

I will tell them in my own way, that of an ordinary guy who, most of the time, didn’t benefit from any privileges to access forbidden zones and just wandered where anyone can go, in the midst of years of North-South nuclear saber-rattling and paranoia.

Several times during this journey along the world’s most hermetic border, I was struck by how many Koreans have completely lost interest in it.

When I published an aerial photo showing the proximity of Seoul-Incheon international airport to North Korea, some South Koreans reacted with amazement: they had never realized it, despite using this airport all the time for business or leisure trips. The owner of a café a few hundred meters from the border, a daughter of North Korean refugees, told me that most of her customers, especially the younger ones, were unaware that the landscape they were watching through the window while enjoying their brunch or sipping their coffee was North Korea.

South Koreans’ apathy towards the other half of their own nation is a well-known phenomenon. In October 2025, for the first time, the proportion of South Koreans who consider reunification ‘unnecessary’ exceeded those who consider it necessary, according to a survey.

Add to this the fact that photography is forbidden in many locations along the border, at a time when a place loses all interest if it isn’t “Instagrammable”, I am not surprised that the overwhelming majority of visitors I met at the border observatories were elderly.

It’s as if we’ve reached a point of no return. But come to think of it, it’s a perfectly human reaction: if you become one of the best educated, richest and most efficient and admired persons in the world, your poor, aggressive and noisy upstairs neighbor is very likely to become the least of your worries. And too bad for your grandparents who knew this neighbor in his youth and would still like to believe he’s salvageable.

I hope my project will not only interest foreigners curious to learn more about the frontier, but that it will also help Koreans to keep alive the memory of this tragic aspect of their nation and their awareness about this never-ending war which, whether they like it or not, will remain part of their subconscious for a long time to come.

Roland de Courson

Seoul, October 2025

Understand

Themes