Understand the Division

A South Korean soldier stands guard at a watchtower overlooking the Imjin River and North Korea (June 2025).

To understand the K-Scar, one must first understand the wound that caused it. Like most injuries, this one was the result of a chain of circumstances both tragic and absurd.

The absurdity: In August 1945, with Japan’s surrender and the end of the Second World War imminent, the United States suddenly wondered what to do with Korea. The country had been under Japanese occupation since 1910. But, as no plan had been prepared in advance to replace the Japanese administration on the Peninsula, the Americans had to improvise.

Time was running out: the Soviets had just declared war on Japan, and the Americans feared the Communist troops would seize the entire Korean Peninsula before them.

Summoned at the Pentagon, two U.S. Army colonels both in their mid-30s, Charles “Tic” Bonesteel and Dean Rusk – who later became Secretary of State to President John F. Kennedy-, were suddenly urged to find out a solution that would suit both superpowers.

In his memoir, As I Saw It, published in 1991, Dean Rusk recounted the surreal night that has shaped the destiny of the Koreans to this day:

“During a meeting on August 14, 1945, the same day as the Japanese surrender, [Bonesteel] and I retired to an adjacent room late at night and studied intently a map of the Korean peninsula. Working in haste and under great pressure, we had a formidable task: to pick a zone for the American occupation. Neither Tic nor I was a Korea expert, but it seemed to us that Seoul, the capital, should be in the American sector. We also knew that the U.S. Army opposed an extensive area of occupation. Using a National Geographic map, we looked just north of Seoul for a convenient dividing line but could not find a natural geographical line. We saw instead the thirty-eighth parallel and decided to recommend that … [Our commanders] accepted it without too much haggling, and surprisingly, so did the Soviets. “

The agreement was initially adhered to strictly. Arriving first in Korea, the Soviets stopped at the 38th parallel and awaited the arrival of the Americans. Each force then proceeded to dismantle the former Japanese colonial administration on their respective sides.

The initial objective for both Moscow and Washington was to give themselves five years to turn Korea into an independent and unified state. But due to the ideological differences between the two great victors of the Second World War and their growing rivalries, this never happened.

A monument marks the 38th parallel, the former border between North Korea and South Korea, in the city of Pocheon (February 2025).

In 1948, the 38th parallel became the boundary between the pro-Soviet Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) in the north, and the pro-American Republic of Korea (ROK) in the south. Each power placed a puppet at the head of its vassal state: the virulent anti-communist Syngman Rhee in the rural South, and, in the industrial North, a communist and anti-Japanese guerrilla leader born as Kim Song Ju who in 1935 had taken the name of Kim Il Sung, meaning “Kim become the sun”. Kim became the founder of a dynasty still in power today.

Since 1910, the Japanese occupiers had concentrated vital industries in the north of the peninsula, where the country’s main raw material reserves such as coal, magnesite, zinc, tungstene and and iron ore were also located, while the south – with twice the population – remained rural and backward. At the time of the creation of the two Korean states in 1948, the South was in an inferior position to the North in every respect.

In the years following the partition, many South Koreans became frustrated with the lack of economic progress and the immobility of their government while, in the rich North, radical socialist reforms were being implemented. The end of the 1940s was a particularly dark period for South Korea, faced with appalling poverty and brutal repression by the Syngman Rhee regime. At the same time, tensions escalated along the 38th parallel, with both sides engaging in border skirmishes and raids.

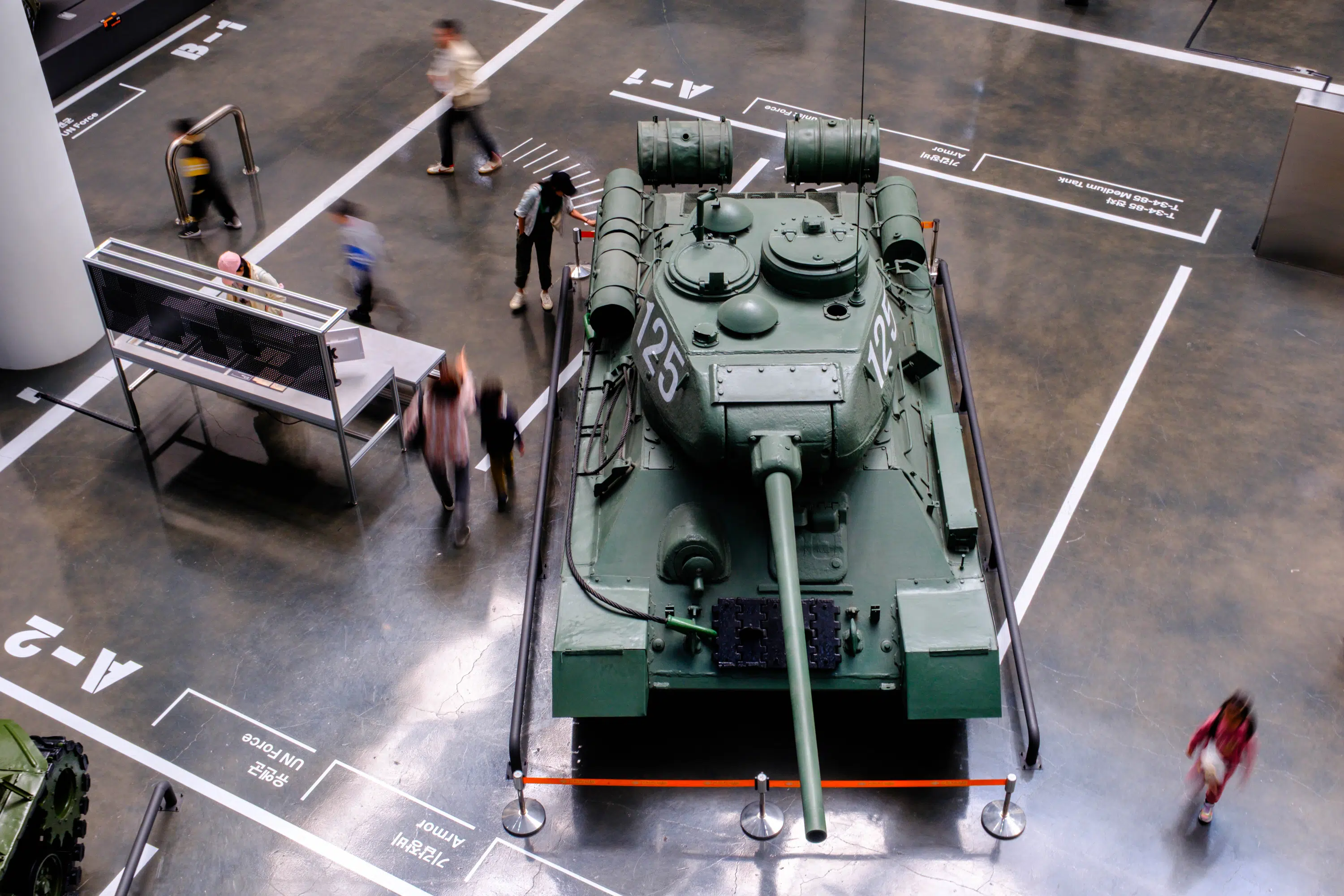

On June 25th, 1950, tens of thousands of North Korean soldiers backed up by a terrifying swarm of Soviet-made T-34 tanks crossed the 38th parallel by surprise, crushing an ill-equipped South Korean army from the outset and taking Seoul in three days. This marked the official start of the Korean War.

The war took place in three phases. The first phase was a near-total destruction of the South Korean forces by those of the North in less than three months (from July to September 1950). The second phase was a dazzling counter-attack by the United States and its allies, which resulted in the near-total crushing of North Korean forces in barely two months (October to December 1950).

Finally, the third phase began with the massive intervention of Chinese forces in support of North Korea, who in the space of seven months recaptured the ground lost up to around the 38th parallel. From July 1951 onwards, the conflict became bogged down in a war of position that lasted two years, with fierce battles and huge losses for minor territorial gains for either side until the armistice agreement of July 27, 1953.

A North Korean T-34-85 tank on display at the War Memorial of Korea in Seoul (April 2025).

At the start of the conflict, the North Korean People’s Army (KPA) was better equipped, trained, and had more combat experience than the South Korean forces. Many of its soldiers were battle-hardened veterans of China’s civil war. Also, prior to the invasion, the United States had withdrawn most of its troops from South Korea and had deliberately left the country’s army under-equipped in order to prevent Syngman Rhee from recklessly attacking the North. In addition, thousands of communist guerrillas sympathetic to the North were operating within South Korea itself.

Within three months, the North Koreans had invaded 90% of South Korea. Only a small pocket around the city of Busan was still controlled by the Singman Rhee government.

Two days after the start of the invasion, the United Nations Security Council passed a resolution recommending military assistance to South Korea. At the time, the Soviet Union was practicing the “empty chair policy” at the UN, so the resolution was adopted without Moscow vetoing it. A UN force led by the United States, the United Nations Command (UNC) was established on July 7, 1950 with 22 countries contributing.

On September 15th the same year, the US staged an ambitious and massive amphibious landing at Incheon, near Seoul and somme 200 kilometers behind the frontline, turning the tide of the war almost overnight.

The plan, devised by UN commander general Douglas MacArthur, was a huge success. The UN forces liberated Seoul ten days later and, instead of just pushing back the North Koreans on their side of the 38th parallel, invaded the north, taking Pyongyang and approaching the Yalu river on the Chinese border.

The Big Chief: the statue of American General Douglas MacArthur in Incheon (March 2025).

It was then that the 1.3 million-strong Chinese People’s Volunteers Force (CPVF), led by veteran general Peng Dehuai, entered the war alongside the North Koreans, inflicting heavy losses to the UN force, pushing it back to the south and retaking Seoul on January 4th 1951 (the capital changed hands for the fourth time in less than one year when the UN troops took it again on March 14th).

For the rest of the war, the fighting continued with large-scale bombings and shellings and bloody battles for positions of little strategic importance along the frontline.

Punctuated by incidents and insults, armistice negociations began on July 10th 1951, first at Kaesong, in the North, then at Panmunjeom, a village on the frontline. These negotiations were not concluded until more than two years later, on July 27th, 1953. On that date, less than five months after USSR leader Joseph Stalin’s death, the United Nations Command, the Chinese People’s Liberation Army and North Korea People’s Army agreed to an armistice.

South Korea, whose President Syngman Rhee wanted to continue the war until the North was crushed, did not sign.

The UN, Chinese and North Korean delegations signed the document and returned to their camps, without even exchanging a handshake.

A Multi-Layered Border

A Military Demarcation Line (MDL) marker at the center of the DMZ in Panmunjom (October 2024).

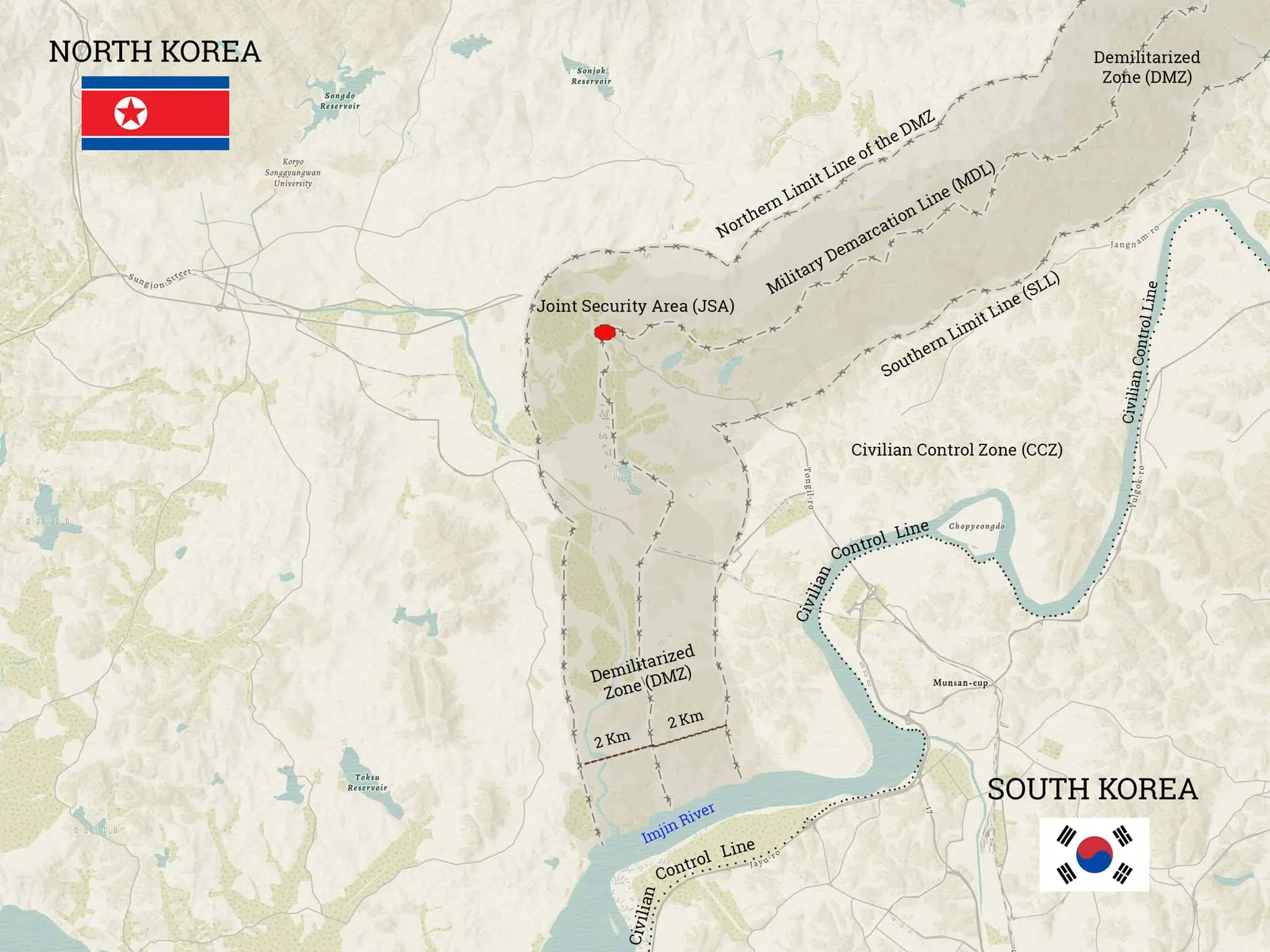

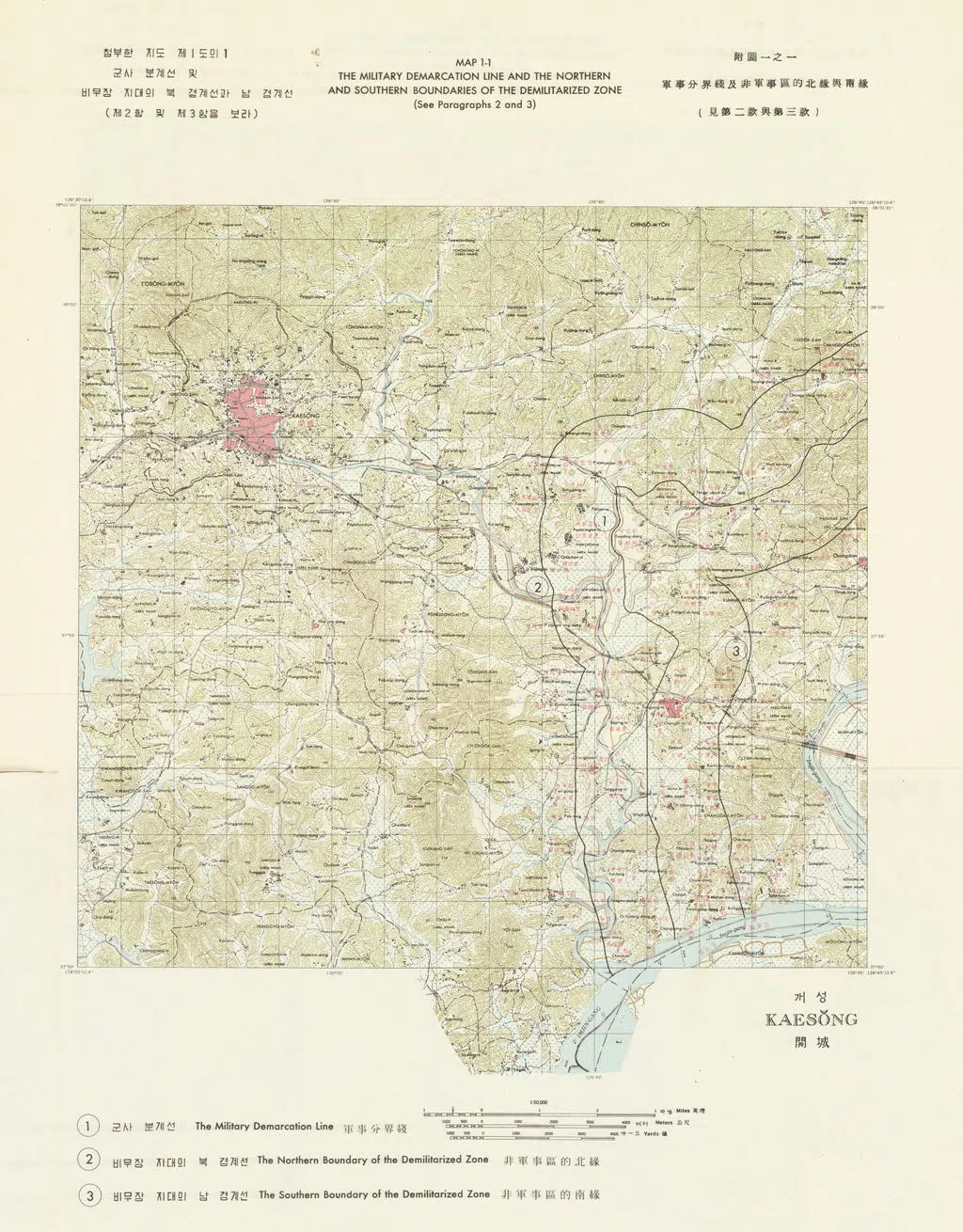

In their armistice agreement, the belligerants accepted to pull their troops back 2 kilometers from the front line, which stretched for 248 km across the peninsula, creating a 4 kilometers-wide buffer zone, called the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ).

The Military Demarcation Line (MDL), the border between the two Koreas, goes through the center of the DMZ and indicates where the frontline was when the agreement was signed.

As the front line did not follow the 38th parallel, towns that had belonged to North Korea before the war, such as Cheorwon and Sokcho in the east, became part of South Korea. Conversely, the large city and ancient capital of Kaesong, located south of the 38th parallel but north of the front line, became North Korean.

The armistice froze a war that had left more than 3 million people dead. But it never ended it. It was a purely military agreement, signed only by army commanders from North Korea, China and the United Nations Force (not even by the South Korean ones), and was never transformed into a peace treaty between governments.

As a result, North and South Korea remain technically at war.

Indeed, the South Korean military continues to refer to the border as ‘the front line’. Since 2024, the North Koreans have stopped using this expression, having officially renounced any prospect of reunification and now considering the Republic of Korea to be a separate, hostile state.

Soldiers from the United Nations Command Security Battalion – Joint Security Area monitor the entry of a tourist bus into the DMZ (October 2024).

The “DMZ” is the world-famous expression for the inter-Korean border. But separation between the two Koreas is in fact made up of a series of ‘layers’, of which the DMZ is the core one, but not the only one.

Dubbed “the scariest place on earth” by former U.S. president Bill Clinton, the DMZ crosses the Korean peninsula from west to east, from the confluence of the Han and Imjin rivers to the Sea of Japan, known to Koreans as the East Sea. Under the armistice agreement, no armed military personnel may enter it.

Soldiers from both sides circumvent this clause by wearing ‘military police’ (MP) armbands to continue to patrol inside the DMZ with their weapons day and night. Also, over the years, both North and South have cut back on the DMZ and set up hundreds of guard posts (GPs) deep inside the buffer zone, usually on mountain tops, to observe the movements of the opposing side. These GPs are generally linked by fortifications or tunnel networks, also built in flagrant violation of the armistice agreement.

In practice, each side does more or less as it pleases. There are no longer any bilateral institutions to peacefully settle disputes, as North Korea has been boycotting them for years for many reasons. Encroachments on the DMZ are so numerous that the acronym no longer means anything. It is in fact one of the most militarized zones in the world, nicknamed “The Z” or “The Devil’s Playground” by the US military.

In the South, each GP is manned by a detachment of between 10 and 30 soldiers. Life at a GP is one of the most intense and psychologically demanding experiences for the military who are stationned there for months in isolation, perform constant guard duty in rotating shifts throughout the day and night and endure harsh weather, limited comfort, monotony and stress.

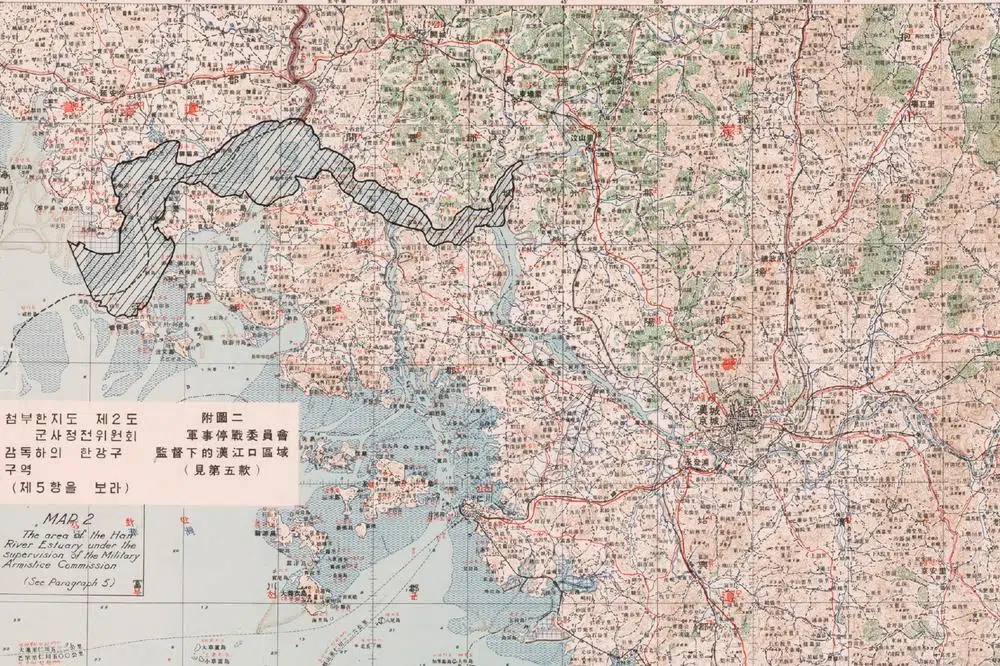

The border area around Panmunjom. The Military Demarcation Line (MDL) marks the border between the two Koreas. On either side is a two-kilometer-wide strip known as the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ), bounded to the north by the Northern Limit Line (NLL) and to the south by the Southern Limit Line (SLL). To the south, an additional strip is a restricted area known as the Civilian Control Zone (CCZ) bordered by the Civilian Control Line (CLL). The small Joint Security Area (JSA) lies at the heart of the DMZ. This is where the two armies face each other just a few meters apart. The map is approximate (Sources: Esri, TomTom, Garmin, FAO, NOAA, USGS, © OpenStreetMap).

The United States maintains a heavy military presence of around 30,000 troops in South Korea, but has pulled back from frontline duties a long time ago with one exception: a combined battalion of South Korean and United Nations troops (mostly American) provides security for the Joint Security Area (JSA). The South Korean military now controls the entire length of the border, much to the anger of the North Koreans, who point out that South Korea never signed the armistice.

Although the South Korean army monitors almost the entire DMZ, access to the area remains exclusively controlled by the United Nations Command (UNC)—effectively the United States. There have been instances where senior South Korean officials have been denied access to the DMZ because they did not request permission from the UNC at least 48 hours in advance. This sometimes causes friction, but the armistice agreement is binding on all parties. In theory, even the South Korean president must request permission from the UNC to visit his country’s soldiers stationed on the front line.

The southern boundary of the DMZ is known as the Southern Limit Line (SLL) or “South Tape”. South Korea began fortifying it in 1967 following an increase of North Korean infiltrations. The initial barrier comprised a 3-meter-tall chain-link fence topped with concertina wire, a cleared 120-meter-wide kill zone with landmines and tanglefoot wire, defensive positions, a raked-sand path that paralleled the fence to highlight footprints and, in some places like the Cheorwon Basin, an anti-tank wall. The fortification efforts were further reinforced in the following years to cover the whole length of the DMZ.

Nowadays, the main fence is topped by intrusion detection nets and comprises thousands of surveillance cameras. Intensive use of night vision gear and other advanced detection systems limits the need for powerful floodlighting of the border at night, as was previously the case.

The “829GP” in Goseong, on the East coast, was the first guard post (GP) established by South Korea inside the DMZ just after the war in 1953. It faces a North Korean GP on the top of a hill only 580 meters away. It has been declared a cultural heritage site by the South’s government in 2019 (November 2024).

In practice, the fortifications often extend much closer to the border than the two kilometers stipulated by the armistice agreement.

These encroachments by the South allow hundreds of thousands of tourists to safely enter the DMZ every year, sheltered by impenetrable barriers which run much further north than they legally should. One of the most visited border attractions, the so-called ‘Third Tunnel of Aggression’ near Seoul, is located 1.2 kilometers from the demarcation line. Some remote military observation posts open to the public, such as Eulji or Typhoon Observatories, are even closer to the border (300 and 800 metres, respectively).

In the middle of the DMZ, the Military Demarcation Line is marked only by 1,292 rusting signs which are placed at intervals. The north facing side of the signs are written in Korean and Chinese and the south facing side in Korean and English.

The Military Demarcation Line and the Demilitarized Zone as set out in the maps appended to the original 1953 armistice agreement.

With the exception of the inhabitants of two villages located opposite each other on either side of the MDL (Daeseong-dong in South Korea, Kijong-dong in North Korea), no civilians live inside the DMZ.

While the villagers in Daeseong-dong enjoy a special status that exempts them from paying taxes and from compulsory military service, Kijong-dong is believed to be an empty ‘propaganda village’. Since the 1980s, two giant flag poles fly the flags of their respective country in Daesong-dong and Kijong-dong.

Beyond the heavily fortified Southern Limit Line is a secondary buffer zone called the Civilian Control Zone (CCZ) that extends to a depth of between 5 and 20 kilometers in South Korean territory. Also known as the “No Farming Zone”, it was created by the US military initially to prevent agricultural activities from disrupting military operations near the DMZ.

The CCZ has shrunk over time, and places like the Punchbowl basin or Cheorwon are no longer part of it. It’s a populated area – there are eight villages within it, most of them rebuilt by the government after the war and allocated to veterans and other deserving citizens- and farming is now allowed inside it.

The South Korean armed forces maintain around sixty General Outposts (GOPs) inside the CCZ. They serve as quick reaction bases in the event of North Korean infiltration or invasion until reinforcements arrive from the rear. Several GOPs have observation posts (OPs) to monitor enemy lines, which are sometimes accessible to the public with authorization.

The CCZ itself is bounded to the south by the Civilian Control Line (CCL) where IDs are checked by the army in both directions.

Civilian visitors may, under certain conditions, move around within the CCZ. What is prohibited or permitted there depends entirely on the local military commander and his level of paranoia.

It is often compulsory to be accompanied at all times by a certified guide or even a military escort. Photography and stops outside a few authorized points are forbidden or severely restricted. The number of passengers in tour buses are counted by the soldiers at the CCL checkpoint on the outward and return journeys. Any discrepancies will trigger a general alert, a total closure of the CCZ and an intense manhunt until the matter is cleared up and the culprit caught.

Where they are tolerated, individual visitors to the CCZ are sometimes given a deadline for their return to the world of the freedom of movement. In certain areas like Yeoncheon, it is necessary to request permission to enter the CCZ at least seven days in advance for background checks.

To access the remote Eulji Observatory located deep inside the DMZ around 300 meters from the demarcation line, civilians need to travel in a convoy escorted by two armoured vehicles. A black tape is affixed to the lens of each mobile phone and a hood to the dashcams of each car, whose trunk and underside is rigorously inspected at a checkpoint in case an intruder is hiding there.

In other places, however, that are also very close to North Korea, such as Gyodong Island, a soldier at a checkpoint simply notes down the identities and license plate numbers of visitors, who are then free to move around as they please.

The CCZ also acts as the final barrier for North Korean infiltrators if they make it past the Southern Limit Line. On the northern side, a 50-kilometer-wide strip along the border has been declared a “special military zone”. However, it is unclear what kind of restrictions apply there, in a country that is itself a “Civilian Control Zone” in its entirety.

“Peace ribbons” on the Civilian Control Line fence at Imjingak (September 2024).

This page was last updated on: January 5, 2026.

Previous : Introduction

Next : Airspace Scares

Understand

Themes